Requirements for Software Architects – Part 3

Modern Techniques of Requirements Engineering

Welcome to the last part of our blog series, where we present the modern techniques of requirements engineering.

Techniques

We have now outlined what constitutes requirements, the journey of a requirement from surveying to architecture, and the stakeholders involved in the process. We have also seen the risks that are entailed if requirements are not given adequate attention.

In the following, we would now like to present a few techniques that can improve or simplify work with requirements.

Agile techniques for creating, maintaining, and prioritizing functional requirements

Product vision

The product vision is the long-term objective that a company strives for. The goal is to create a product that serves a purpose. The product vision describes the expected outcome, i.e., the “what”.

One of the best and most clearly formulated visions comes from J.F. Kennedy – the first landing on the moon.

Figure 1: President Kennedy speaks to Congress on May 25th, 1961

Figure 2: Commander Neil Armstrong working at an equipment storage area on the lunar module, Credits: NASA

A team with a good, clear, tangible product vision can develop a better product than a team without a vision or with only a vague idea of where they are supposed to go.

Stakeholder analysis

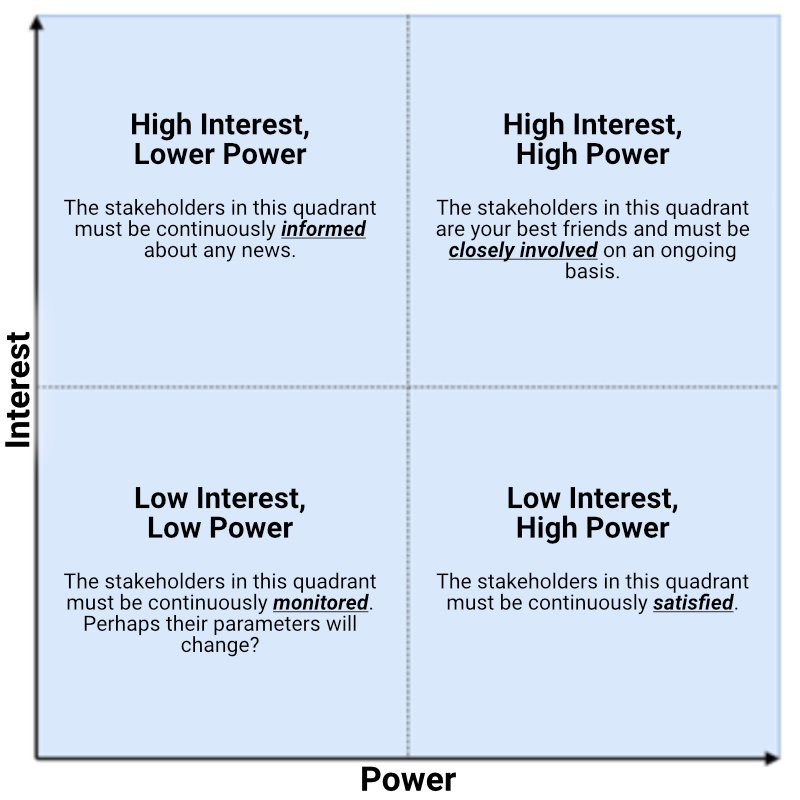

Identifying the people who participate in a project is one of the most important tasks of a Product Owner (BA, RE) and software architect. There are many different methods for conducting a structured stakeholder analysis. The Stakeholder Matrix can be a tremendous help in specifically identifying stakeholders:

Figure 3: Stakeholder assessment – how do I deal with my stakeholders?

Monitoring (low interest, low power and thus impact):

These stakeholders should be specifically informed without sharing irrelevant information with them. Carefully coordinating communication with these partners is necessary to ensure relevance.

Satisfaction (high power, low interest):

It is important to invest adequate time in these stakeholder groups to ensure their satisfaction but without making them feel overloaded.

Inform (low power, high interest):

Inform these stakeholders accordingly and gather the relevant information to prevent greater problems. Stakeholders of this category often look at project details critically.

Remaining in close contact (high power, high interest):

These stakeholders are the main players. They should be fully integrated into the project. Take enough time to satisfy them.

Persona

Personas are used to attempt to describe a particular type of user. During the process, you put yourself in the person’s shoes to understand their situation and use that information to define their needs. A persona is a useful tool to survey requirements. It often makes sense to use it if customer surveys (a tool for surveying requirements) cannot be carried out. Furthermore, personas are used with major products/systems that are used by broad groups of end users.

Example:

Mathias is forty-five, married, and has two children. He works as a quality manager for the German Federal Labor Office (Bundesagentur für Arbeit). He takes the train from Mannheim to Frankfurt every morning and is proud to have made a significant contribution to the office’s efficiency and effectiveness for 15 years. In his free time, he spends time with his friends in a restaurant in the city’s historical center, where they hold lively discussions and share mutual interests.

This is a rather brief example of a persona description. In practice, it can often fill entire pages. When documenting personas, it is important to empathize, i.e., take into account special details and emotions. This is the only way to properly understand a customer or end user.

Agile techniques for documenting requirements

Use cases

Use cases describe a requirement or product features from the customer’s perspective.

The objective is to receive an (initial) description, in the customer’s language, of the functionality of the product to be developed.

This has some advantages:

- Customer needs can be understood better and properly since they are expressed in their own words.

- It is a good basis for making decisions on prioritizing requirements

- Misunderstandings are reduced to prevent any undesired requirements from being added to the product.

- Scope: Add only what is supposed to belong in the system

After defining the different use cases that have been formulated by the customer or together with the customer, these use cases can be described in greater detail and refined.

This is where use case documents (name of the use case, preconditions, normal procedure, alternative procedure, postconditions) and UML (e.g., use case diagram, activity diagram) come into play to illustrate and visualize the requirements for the system. Additional diagrams for illustrating and defining internal structures and processes are also depicted in the later steps (software architect role) for the purpose of visualizing the software architecture.

User stories

User stories are concise descriptions of a feature from a user perspective. It is important to formulate them in one to two sentences.

The stories are supposed to tell why the user requires a particular functionality and which objectives or benefits they can obtain with it. Unlike classic techniques in requirements engineering, the user story does not specify the solution for how the feature is implemented. Rather, it only specifies what is implemented (required). The user story does not describe the “how”—it only describes the “what”. The user story is supposed to document the background, rationale, objectives, or benefits of why this particular feature should be implemented.

A sentence template has been established in the agile environment. It specifies that there are always three primary elements that illustrate the value of a functionality as it is used: Role, Feature and Rationale (value/benefit, etc.).

It can be formulated as follows:

As a <Role>, I would like a <Feature>, because <Rationale>

As a <Rolle>, I would like <Feature>, to obtain <Benefit/Value>.

Examples:

- As a passenger who travels back and forth, I would like to re-book frequently booked train routes as quickly as possible to save time while booking.

2. As a human resources manager, I would like to be able to sign vacation requests directly in the system to approve the vacation without having to download vacation requests.

Agile techniques for specifying user stories

Story mapping

Prioritizing requirements and maintaining product backlog items (=PBI) are part of a Product Owner’s day-to-day tasks. Story mapping is an excellent tool for overcoming this challenge.

This method can be used both at the beginning to derive user stories in the first place, and during the development process. Since development in the agile environment is always conducted iteratively and gradually, new user stories are created after each round of customer feedback or required modification.

A story map consists of two dimensions (horizontal and vertical). The first horizontal dimension includes the rough requirements, and the second vertical dimension refines these requirements. The deeper you go, the greater the increase in the level of detail. The goal is to break down a requirement – from the customer’s perspective – into refined and small tasks in order to subsequently implement them. Therefore, story mapping can be regarded as a management technique.

Agile techniques for managing requirements

Epics

The created user stories can now (or, alternatively, in a prior step) be summarized in epics. These epics group together related user stories. During the process, for instance, they are summarized based on higher-level business objectives or the ability to offer them as standalone, priced services. For example, user stories such as “Application for child benefits”, “application review by clerk”, and “child benefits payout” can be bundled under the “child benefits management” epic.

Advantages:

- “Divide et impera”: The entire system to be developed can be documented in subsections at the beginning of the project.

- Project structuring, i.e., parts of the system can be abstractly described at the beginning of the project without having to go into detail at an earlier stage.

- One important benefit in using epics is the control over the specialist concept or product backlog (list of user stories). Otherwise, you can quickly lose track of things in major projects associated with a product backlog with hundreds of user stories.

Techniques for identifying architecture-related requirements

Some of the most effective methods for determining ASRs are:

- Questionnaires/checklists

- Stakeholder surveys

- Quality attribute workshops (QAW)*

Structured interview

A structured interview can help to identify blind spots, specifically when surveying non-functional requirements, and is conducted individually with stakeholders. Nevertheless, the relevance of the identified requirements for the architecture must still be assessed after an interview. Requirements also help to derive a measurable and crucial characteristic (e.g., in the form of a quality scenario) in a manner that is not yet mandatory. However, this can also be carried out as part of interviews with stakeholders as needed.

This technique is useful since there are many arrangements and categorizations of possible quality requirements. Designing the survey based on existing configurations often helps stakeholders to identify requirement areas that they have previously not taken into account.

For instance, some models for structuring quality characteristics include

- ISO/IEC 25010

- The “ilities” model

- Q42

Here is an example of how an interview can transpire:

For the interview, an exemplary system requirement is prepared for each category.

Afterwards, the objective of the interview and the methods are presented to the stakeholder.

Next, the model is reviewed category by category together with the corresponding stakeholder. If this stakeholder is already aware of requirements in this category, then a category is omitted as needed.

During the process, all the created requirements are documented. When documenting the requirements, questions are also asked on how the requirement helps the stakeholder achieve his/her objectives. As a result, the relevant of the requirement is verified since this type of interview runs the risk of creating an excessive number of requirements. Furthermore, it will be possible to obtain an overview of the stakeholder’s underlying interests. Lastly, the stakeholder is thanked for their time.

After the interview, the documented requirements are reconciled with existing documentation and new requirements are documented. If the requirements contradict previously documented requirements, then consultations are held with the stakeholder and, if necessary, the PO, BA, and RE. Lastly, the architectural importance of the requirements are assessed.

Techniques for documenting requirements

BDD

Behavior-driven development, also known as requirements-driven software development, was first described by “Dan North” in 2003 and has since continued to grow. Dan North also developed the first framework for implementing BDD in JBehave.

BDD is another agile software development technique that improves collaboration between different participants in software development projects—particularly in the Software Architect/Product Owner/Business Analyst team. In behavior-oriented (behavior-driven) development, software tasks, objectives, and results are documented in a defined text form during requirement analysis that can afterwards be carried out as automated tests.

By doing so, you can verify if the software has been properly implemented or if additional adaptations are required.

Software requirements are formulated in scenarios, typically known as “if-then” clauses. This approach is based on the language of domain-driven design (DDD).

The objective is to develop a mutual understanding and make it easy to transition from technical requirements to implementation.

According to BDD, a format that is derived from the user story specification (“As” role…) is used for the behavior specification.

Each user story should follow the structure below to some extent:

Title

An explicit title

Narrative/Explanation

A brief introduction with the following structure:

As: The person or role who benefits from the function;

I would like: the function/feature;

so that: the benefit or value of the function.

Acceptance criteria

A description of each specific scenario of the story with the following structure:

Given: The starting context at the beginning of the scenario in one or several sections;

When: The result that triggers the scenario;

Then: The expected result in one or several clauses.

Example:

Scenario 1: Returned goods are placed in stock again

- Given the customer has purchased black pants

- and we subsequently had three pairs of black paints in stock,

- If the customer returns the pants and receives a credit for it,

- Then we will have four pairs of black pants in stock.

It is advisable for the software architect, business analyst, and developer to work together to draft the scenarios and document the resulting outcomes in a separate document.

Summary

Requirements are one of, if not, the main driving factor of software development. This is why collecting, documenting, specifying, and administering requirements is one of the most important activities in software development.

Nevertheless, even good requirements do not guarantee success, as we can see in the dynamics between surveying requirements and declaring them as relevant for architecture. Open communication and a mutual understanding about the requirements and what is produced using these requirements – including the corresponding acceptance processes – are also essential.

This indicates the need for the Requirements Engineer, Product Owner, Business Analyst, and Software Architects to collaborate and find a mutual language and basis to make the requirements consistent in the interest of the project’s success—not just once but rather iteratively and continuously.

And this concludes our blog series on requirements for software architects. Thank you very much for reading!

Sources:

- Sommerville, Ian (2009). Softwareengineering (9th ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978–0‑13–703515‑1.

- Andreas Wintersteiger, Scrum Schnelleinstieg [a quick introduction to Scrum]

- McGreal, Don; Jocham, Ralph (June 4, 2018). The Professional Product Owner: Leveraging Scrum as a Competitive Advantage. Addison-Wesley Professional. ISBN 9780134686653.

- https://t2informatik.de/

- North, Introducing Behaviour Driven Development

- Dan North et al.: Question about Chapter 11: Writing software that matters. (no longer available online.) Archived from the original on November 7, 2009; retrieved on November 9, 2011: “The phrase ‘BDD is TDD done well’, while a nice compliment, is a bit out of date. […] BDD has evolved considerably over the years into the methodology we describe in the book. Back when it was focused purely on the TDD space– around 2003–2004 – this was a valid description. Now it only covers a small part of the BDD proposition”

- Schwaber, Ken; Sutherland, Jeff (November 2017), The Scrum Guide: The Definitive Guide to Scrum: The Rules of the Game, retrieved May 13, 2020

- “Lessons learned: Using Scrum in non-technical teams”. Agile Alliance. May 18, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- Ken Schwaber; Jeff Sutherland. “The Scrum Guide”.org. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- https://www.scrum.org/

- http://agilemanifesto.org/

- https://www.isaqb.org/

- https://swissq.it/agile/die-rollen-des-po-re-und-ba-im-vergleich/

Figures:

Figure 2: https://astrobiology.nasa.gov/missions/apollo-11/

Figure 3: Stakeholder assessment— how do I deal with my stakeholders? | Felix Klauke (medium.com)

This is a translation of ITech Progress’ blog post “Requirements for Software Architects – Moderne Techniken des Requirement Engineerings”. Here you can find the original blog post in German.